A look back

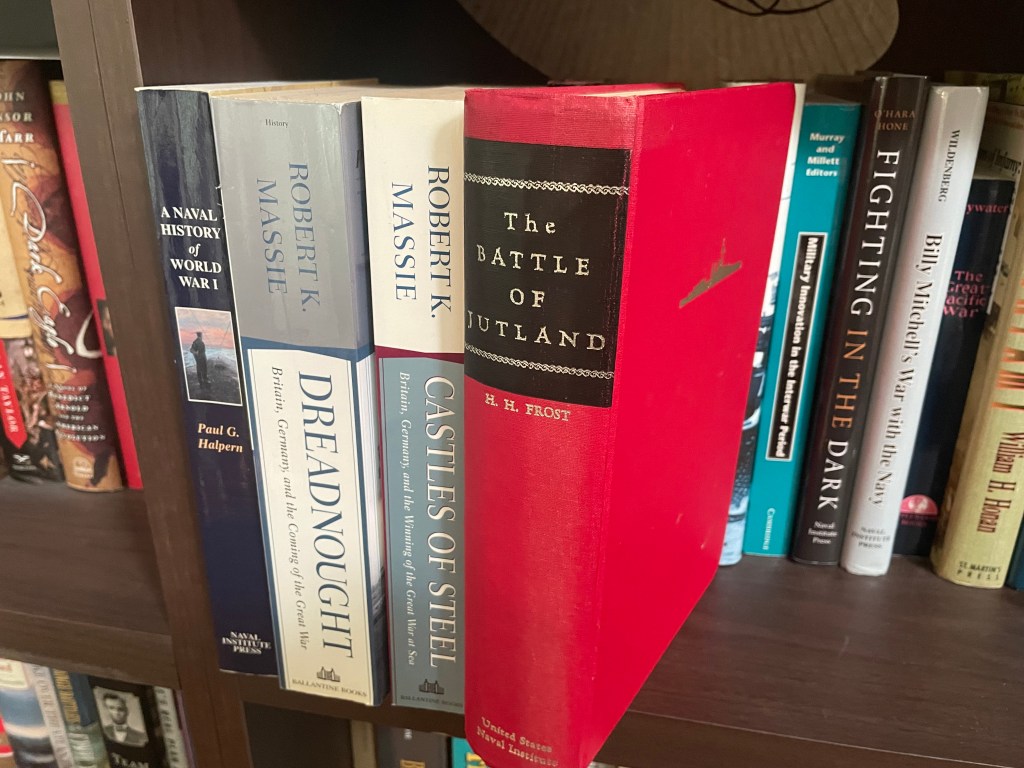

As I was reading The Battle of Jutland by Commander Holloway Halsted Frost, U.S. Navy, I came across this review in the March 1936 issue of Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute. Simply put, I cannot write a review any better.

THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND. By Commander Holloway Halstead Frost, U. S. Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: U. S. Naval Institute. 600 pages. 1936. $4.50.

Reviewed by Professor Allan Westcott, U. S. Naval Academy

In Winston Churchill’s often quoted words, Admiral Jellicoe was the only man who “could have lost the war in an afternoon.” Perhaps—though this will be disputed—the statement would be equally true if the words “could have lost” were replaced by the words “could have won.” Compared with engagements on land, the stakes at issue in the Jutland battle, as in many other famous naval actions of history, were far out of proportion to the man power or even the fighting power involved. Around it, as around Trafalgar, there has already grown up a whole library of records, reports, narratives of participants, criticism, and bitter controversy. Yet in the case of Trafalgar, it will be recalled, the actual tactics employed, the position of ships and their movements, were not definitely established until an Admiralty commission was set to the task after the lapse of a hundred years, and in certain minor details they remain unknown even today.

For Jutland, this fixing of what may be called the factual details of the action has been one of the great services rendered by the late Commander Holloway Frost. As most of his fellow-officers know, he was from the time it was fought an ardent student of the battle. His charts, first published in the Naval Institute Proceedings in 1919, were drawn necessarily from the incomplete and often erroneous information then available. But constant process of study and revision since that time, involving the preparation of at least a dozen sets of sketches, correspondence with leading participants, and employment of all available material from both British and German sources, has made them today probably the best representation of the battle that we shall ever have. Thus the 11 sketches and 60 figures or plans assembled in the present volume are alone worth many times the price of the volume to every naval officer and to every student of naval history.

Frost brought to his study of Jutland, however, not only an unequalled knowledge of what actually happened, but an excellent background of professional experience including much staff service in war time and later, an alert critical faculty, and a completely unbiased point of view. His book does not argue a thesis or plead a cause. But on every phase of the battle and every decision reached he expresses freely his own critical opinion or interpretation of the lesson to be drawn. Instances may be taken almost at random. Thus on Jellicoe’s policy embodied in his famous letter of October 30, 1914, and approved by the Admiralty:

How so aggressive a leader as Churchill consented to such a defensive attitude in complete variance with the Nelsonian tradition is a mystery that has never been explained.

Or on the leadership in the battle:

Scheer’s remarkable resolution and particularly his night movements have our full commendation, but his numerous tactical mistakes during the latter part of the day action prevent his being called a skilled tactician…. As between Jellicoe and Scheer, we believe in general that Jellicoe executed a poor conception of war excellently, while Scheer executed an excellent conception of war poorly.

These are of course in the nature of final judgments rather than analyses; needless to say, the tactical errors referred to, such as those involved in Scheer’s “capped” position shortly after 7:00 p.m. and his employment of the battle cruisers at that time, had been previously treated in detail. Critical judgments are also mingled with an almost romantic appreciation of striking or heroic achievement.

With such judgments the reader may not agree. Agreement is not at all essential. In fact the chief value of Frost’s book lies not so much in its excellent body of information as in its frank critical commentary, which constantly prompts the reader to profitable thought and analysis of his own. While the gain here is primarily for the professional student, discussion of this nature has a fascination also for the general reader, such as is always to be found in the study of great military leaders and campaigns.

At Jutland the opposition was more equal, if we except certain single-ship and small-squadron engagements of our own wars with Britain, than in any important naval action since the Anglo-Dutch wars. And if the leadership at Jutland was less inspiring than at Trafalgar, the lessons are likely to be more profitable, especially as the battle affords a closer approach to the weapons of today. It would have been convenient if the author had taken these lessons, as pointed out in the course of the volume, and summarized them in a concluding chapter. This is a service which now invites some competent student in the professional field.

Although it is a matter of deep regret that Commander Frost could not have seen through its last stages this labor of nearly a score of years, it may be added that the editorial supervision has been carried out with the utmost care. The illustrations include portraits of Admirals Jellicoe, Beatty, Scheer, and Hipper, together with pictures of the chief ship types employed in the battle. Appendices give the complete fleet organization of the two forces, characteristics of the capital ships, and the personnel losses of both fleets. There is a most comprehensive bibliography and an excellent index. Included in the prefatory material is a foreword by Rear Admiral David Foote Sellers, former Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, on whose staff Frost served as operations officer. The foreword ends as follows:

Having known Commander Frost as well as I did, I feel that his description, maps, opinions, and stated conclusions are based not only upon the very highest authority obtainable but are the result of a critical analysis only possible to a man of his high professional attainments.

Proceedings, Vol. 62/3/397

De-Frosted thinking

When Commander H.H. Frost died in 1936 at the young age of 45, the U.S. Navy arguably lost one of their greatest thinkers. The Battle of Jutland was Frost’s magnum opus. As Edwin A. Falk writes in the Prefatory Note to the 1936 (and later 1964) editions, “This book is a product of eighteen years’ work, commencing shortly after the Battle of Jutland” (Frost, ix).

All the Navy knew Frost was destined for greatness. Graduating Annapolis in 1910, in 1916 then Lieutenant (junior grade) Frost was ordered to the U.S. Naval War College—the youngest officer ever appointed there. Lest you think Frost sat comfortably in the halls of academia, he had plenty of fleet experience in World War I when he was Senior Aid and Operations Officer to Admiral Edwin A. Anderson, veteran of the Spanish-American War and Congressional Medal of Honor winner, who led the American Patrol Detachment of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Frost followed Anderson when he was later assigned as Commander of U.S. Naval Forces in European waters and eventually the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. Frost went on to serve as Operations Officer to Admiral David Foote Sellers when he was Commander U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Frost also served in destroyers (wrote a book about them too), was qualified to command submarines, and was designated a Naval Aviator.

Yet, for Frost the Battle of Jutland always seemed to hold a special interest. His earliest work on the battle dates from 1919 when he was at the Naval War College. As a result of an article on the battle published in Proceedings in 1919, Frost opened correspondence with many of the actual participants such as Admiral Sheer and Admiral Hipper. In 1927, when Frost was assigned as a naval expert at the Geneva Conference in Europe, he vacationed in England and Germany and met many other personalities connected to the battle. Between 1927 and his untimely death in 1935 Frost wrote and sketched the book that eventually became The Battle of Jutland published shortly after his death.

Some readers might ask if The Battle of Jutland—a book on a battle from World War I written in the mid-1930s—has any relevance to today’s navy. This was the question posed to the publisher of the 1964 edition who asked: “…for what professional reason would an officer study the Battle of Jutland—a large, indecisive action fought in the mists of the North Sea more than half a century [now more than a century] ago?” (Frost, p. xiii). The reasons given in 1964 are still relevant today:

- “Any fleet or field commander can appreciate the frustration caused by ‘…the futile attempts of the Admiralty to direct tactical operations from a distance.’ This problem continues today, but in 1916 it was a new and untested tactical consideration” (Frost, p. xiii).

- “German communications security was bad; British intelligence was good and knew how to take advantage of that German failing, so the British always knew when the Germans intended to go to sea and were ready to meet them. Many who fought in more recent wars know of that this situation can as easily happen now as it did in 1916” (Frost, pp. xiii-xiv).

- “There were the interesting situations and attitudes of the commanders: the German leader, Scheer, who commanded a force too expensive and too powerful to remain unused but too weak to succeed in any important way, and his rival Jellicoe, a man who, through his determination not to risk defeat, insured that victory was unobtainable” (Frost, p. xiv).

The 1964 Publisher’s Preface to The Battle of Jutland notes, “[Frost] had spent eighteen years collecting material for this book, much of it by interviewing participants whose observations and memories might otherwise have been lost forever” (Frost, p. xiv). While historians may not consider The Battle of Jutland a primary source, the proximity of the author in time and relationship to the participants makes this book a most valuable secondary source; indeed, after a century and a second world war, the contents of The Battle of Jutland may be the only place some of that original knowledge remains.

RECOMMENDED

See also Frost’s Diagrammatic Study of the Battle of Jutland published by the Office of Naval Intelligence in 1921.

Book

- Frost, H. H. (1936, 1964) The Battle of Jutland. United States Naval Institute.

Related wargames in the RMN collection

- Benninghof, Dr. Michael and Doug McNair (2006, 2016, 2023) The Great War at Sea: Jutland. Avalanche Press.

- Carson, Chris and Michael Harris, Ed Kettler (2001) Fear God & Dread Nought. Clash of Arms/Admiralty Trilogy Group.

- Dunnigan, Jim (1967. 1974) Jutland. The Avalon Hill Game Company.

- Gill, L.L. (1975) General Quarters. NavWar Productions.

- Graber, Gary (2007) Battleship Captain. Minden Games.

- Greene, Jack (1984) Royal Navy. Quarterdeck Games.

- Hardy, Irad B. and John Young (1975) Dreadnought: Surface Combat in the Battleship Era, 1906-45. Simulations Publications, Inc.

- Sartore, Richard and Jack L. Joyner, R. A. Nadeau (1981) Seekrieg, Fourth Edition. Xeno Games.

- Newberg, Stephen (2006) Line of Battle, Second Edition. Omega Games.

- Wilcox, Stephen G. (1984) Battlewagon. Task Force Games.

Feature image courtesy RMN

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Service, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2025 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0