Grok’ing Zweibelson

Reconceptualizing War is a dense book. The hardcover is a “mere” 742 pages. It is also written at a very high academic level. Working my way through Reconceptualizing War has been a tough slog for me. I try to get through one book a week but the length and depth of this book has slowed me down meaning I am already in week two and looking at a third.

It was a welcome moment when I saw the author themself post a summation of Reconceptualizing War at their Substack page Sapiens, Technology, and Conflict: Ben Zweibelson’s Substack. In the newsletter “I gave Grok4 the entire ‘Reconceptualizing War’ manuscript and asked for an unbiased 1,000 word or less review; here is what Grok gave me” delivered the following:

Reconceptualizing War: A Philosophical Lens on Humanity’s Endless Conflict

By Ben Zweibelson

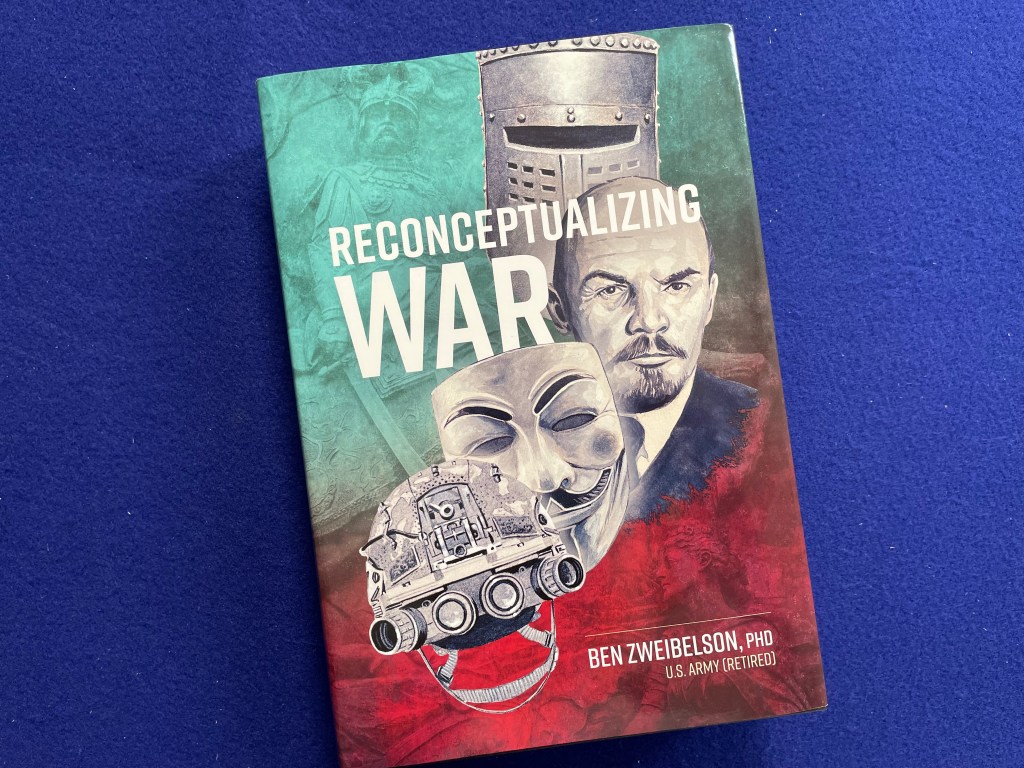

Helion & Company, 742 pages, $59.95

In an era where drones strike from afar, cyber skirmishes erode borders, and ideological battles rage on social media, war feels both omnipresent and elusive. Ben Zweibelson, a retired U.S. Army officer turned philosopher of conflict, argues in “Reconceptualizing War” that our understanding of this ancient scourge is trapped in outdated frames. Drawing on sociology, philosophy, and complexity science, he proposes a meta-theoretical overhaul: viewing war not through a single lens, but via four competing “social paradigms” that reveal humanity’s fractured perceptions of violence. It’s an ambitious, sprawling work that challenges military orthodoxy and invites readers to rethink everything from Clausewitz to cyberterrorism. But does this reconceptualization illuminate the fog of war, or merely add to it?

Zweibelson, who has advised on military design and strategy for organizations like the U.S. Special Operations Command, isn’t writing a conventional history or tactical manual. Instead, he builds on the foundational work of sociologists Gibson Burrell and Gareth Morgan, who posited four paradigms—functionalism, interpretivism, radical structuralism, and radical humanism—to explain organizational behavior. Zweibelson adapts this to war, synthesizing it with the overlooked philosophies of Anatol Rapoport, a game theorist and peace advocate exiled from military academia for his heretical views during the Cold War.

The book’s structure mirrors this framework. After introductory chapters laying out social paradigms and Rapoport’s tripartite philosophies (political, eschatological, and cataclysmic), Zweibelson devotes deep dives to each quadrant. Functionalism, the dominant Western paradigm, emerges as a scientifically rationalized view rooted in Enlightenment thinkers like Kant and Newton. Here, war is a calculable extension of politics, epitomized by Clausewitz’s trinity and Jomini’s geometric principles. Zweibelson traces its evolution from Napoleonic battles to cybernetic theories in Vietnam, critiquing how it privileges state sovereignty and technological determinism—think Effects-Based Operations or nuclear deterrence—while blinding practitioners to cultural nuances.

Radical structuralism, by contrast, channels Marxism’s historical materialism, where conflict drives class evolution toward utopia. Zweibelson explores Lenin, Mao, and Che Guevara, showing how guerrilla warfare and proletarian revolutions invert functionalist hierarchies. He extends this to anarchism and eco-terrorism, groups like the Earth Liberation Front that seek systemic overthrow through violence. Radical humanism, splintering from Marxism via the Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse), weaponizes critical theory for activism: “wokefare,” as Zweibelson dubs it, where intersectionality and postmodern critique dismantle oppressive structures, from antifascist movements to queer theory in security studies.

Finally, interpretivism offers a subjective, context-bound antidote, drawing on Weber and postmodernists like Baudrillard. War here is never fixed; it’s a river you can’t step in twice, shaped by symbols, narratives, and emergent complexities. Zweibelson urges “multiparadigmatic” synthesis—blending these incommensurate views for innovative strategies—warning that single-paradigm rigidity dooms militaries to repeat failures like Iraq or Afghanistan.

Zweibelson’s interdisciplinary breadth is the book’s chief strength. He weaves ancient Chinese strategists like Sun Tzu and Guiguzi with modern phenomena: al-Qaeda’s eschatological jihad, Aum Shinrikyo’s doomsday cult, or Anonymous’s cyber-anarchism. Case studies, from the Danish resistance in World War II to Hamas’s ideological warfare, ground abstractions in gritty reality. His prose, though dense with jargon (ontologies, epistemologies), is lucid and passionate, dedicated to “brothers and sisters in arms” scarred by conflict. This isn’t armchair theory; Zweibelson’s combat experience lends authenticity, and his call for reflective critique echoes Rapoport’s quest to avert nuclear doom.

Yet the book’s ambition invites flaws. At over 700 pages, it risks overwhelming readers outside academia or defense think tanks. Paradigm incommensurability—Zweibelson’s core tension—feels unresolved: if these frames are truly incompatible, can synthesis avoid superficial eclecticism? Critics might argue he glosses over ethical pitfalls, like how multiparadigmatic thinking could empower extremists. And while he nods to future disruptions—artificial general intelligence birthing an “artificial war paradigm”—these feel speculative, more sci-fi than scholarly.

Still, in a world of hybrid threats and eroding Westphalian norms, “Reconceptualizing War” is a vital provocation. It won’t end conflicts, as Zweibelson admits, but it equips strategists, policymakers, and scholars to navigate them with humility. For those weary of doctrinal echo chambers, it’s a paradigm shift worth the effort. As Rapoport might say, how we think about war shapes whether we survive it.

(Word count: 748)

Impressed

On the Grok4 review of Reconceptualizing War, Zweibelson writes, “So, the above review is the unvarnished offering from Grok4, and I have to say that I am impressed.” They go on to comment:

There are no errors that I can spot, although I just did a similar test-run with my latest book, ‘Bad War Stories’, and Grok4 did insert a few hallucinations and clear errors into that critique. For this one, I wondered if the larger file size and deeper complexity of the topic might trip Grok4 up in a few spots. In this test, it really was a solid and rapid result. Do I disagree with Grok’s critiques that the book does not deliver in a few areas of ethical pitfalls? Sure- but I cannot argue with the fact that this reads like a legitimate book review.

While Zweibelson may be impressed, I am still a bit overwhelmed by Reconceptualizing War. Now that I know the author considers the Grok4 review somewhat reasonable I have a framework to help me as I continue reading. Maybe my reading will accelerate a bit and my understanding will increase…thanks to Grok.

Wargaming Connection

As the Grok4 review of Reconceptualizing War notes, “At over 700 pages, it risks overwhelming readers outside academia or defense think tanks.” No kidding! This equally, if not more, applies to wargamers and in particular wargame practitioners who might be seeking insight from the book. Before one can wargame Zweibelson’s “multiparadigmatic synthesis” one has to understand it. If my slog is an exemplar of the effort needed to first read, if not understand, the book then understanding will come slowly. Reconceptualizing War might show a new way of war but finding the baseline understanding of such will come only after a great effort is first taken to simply decipher what Zweibelson views is being synthesized.

Feature image courtesy RMN

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2025 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

nice touch using the singular “they” for Zweibelson!