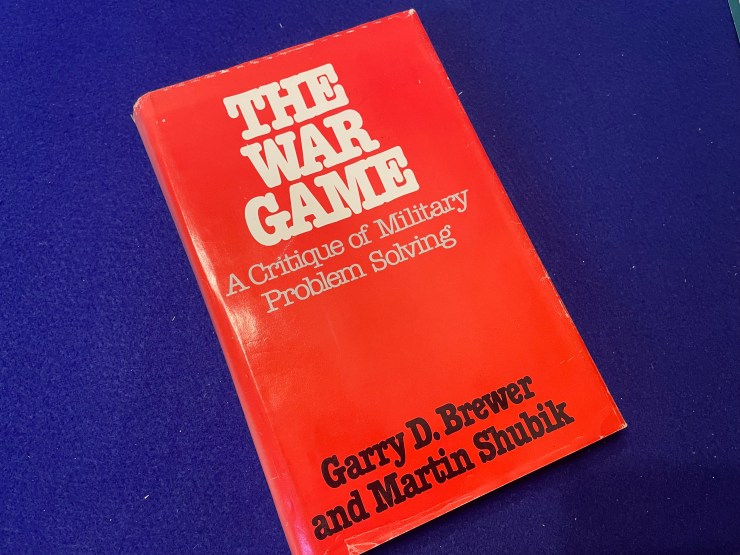

In 2015, then-Deputy Defense Secretary Robert Work energized the world of defense wargame practitioners in a call to revitalize wargaming. Alas, Work’s clarion call to the wargame practitioner community was not the first. The War Game: A Critique of Military Problem Solving by Garry D. Brewer and Martin Shubik (Harvard Press, 1979) made similar calls in the late 1970’s. Perhaps the most disappointing part of reading The War Game is just how many of the recommendations made to improve defense wargaming are still relevant—and needed—today.

Wargame critique

The very beginning of the Preface in The War Game feels as it it was written today and not 45 years ago:

The military analysis system is fragmented, large, even inchoate; it considers topics often highly technical, if not esoteric. The institutions active in the field vary greatly; they are public, private, profit-making, nonprofit, military, civilian, and intricate hybrids and combinations of these types. The individuals responsible for the system represent a broad spectrum of academic and professional specialties and range from physicists who worry about the effects of modern weapons of war to historians who try to make sense of past conflicts.

Brewer & Shubkin, p. xi

As the preface continues: “The War Game began in August 1970 as a broad inquiry into the state of operational modeling and gaming in the United States” (Brewer & Shubik, p. xi). This inquiry originally was a RAND study report that was repackaged into the book.

As is to be expected, The War Game provide a definition for a “war game” that reads this way:

War gaming. One of the major applications of simulation is war gaming. A war game is defined by the Department of Defense as a simulated military operation involving two or more opposing forces and using rules, data, and procedures designed to depict an actual or hypothetical real-life situation. It is used primarily to study problems of miltary planning, organization, tactics, and strategy. A war game can be designed to cover the entire spectrum of war—politicomilitary crises, general war, or limited war. The game may be based on hypothetical situations, real-world crises, or current operational and contingency plans. Some games are designed for joint use by two or more military services; some, for use by a single service. Others may be used by individual field commanders or even by divsion or battalion commanders. The level of command at which the game is to be played influences the type of units represented and the scope of operations conducted.

Brewer & Shubik, p. 8

As denoted by the subtitle, The War Game is not only a review of the “state-of-the-art” of defense wargaming in the United States in 1979 but also a set of recommendations for improvement. As the authors write:

Making recommendations is a hazardous occupation. The practitioner who puts forth his suggestions may be accused of a lack of objectivity, while the nonpractitioner who dares to speak out may be accused of not knowing enough. Nevertheless, we sincerely believe that the use of military models, simulations, and games is extensive enough and the potential value of work in this area is great enough that many separate, interrelated changes must be considered in professional standards and practices, in managerial stewardship, and in the performance of the entire system responsible for these devices.

Brewer & Shubik, p. 259

Amateurs to arms

In the book Numbers, Predictions & War by Colonel Trevor N. Dupuy (U.S. Army, Ret.) and published contemporaneously with The War Game in 19791, three groups were identified as the core elements of the wargame practitioner community. As Dupuy identified them:

- “First there is what I call the Defense Reserch Community, a disparate group of people in Government, in research organizations, and in defense industry; most of these are OR [Operations Research] analysts, but the group also includes a few serious military historians, military planners, and military bureaucrats in and out of uniform, serving in the Defense Department or the armed services, or subsidiary agencies.”

- “Second are the military professionals—including planners and civilian bureaucrats, of course—of the several services, most of whom are somewhat removed from tht day-to-day use of OR techniques, but who find themselves increasingly affected by OR analysis.”

- “The third group consists of military ‘buffs’ who are civilians (although they may have formerly been in uniform or civilian jobs in the military establishment) who are interested in military matters. Particularly important in this later group are the war game enthusiasts, most of whom are as much interested in games that portray, with reasonable accuracy, military operations of the historical past, as they are in models that appear to project and predict warfare in the future.” (Dupuy, pp. ix-x)

Interestingly, though Dupuy identifies hobby wargamers as a member of the wargame practitioner community, The War Game is remarkably quiet on their contributions. Commerical hobby wargames are mentioned only two times in The War Game. The first mention is a passing comment in a section discussing Diagrams and Maps which reads:

Board games used for entertainment are frequently related to or, in some cases, are map war games. The board game Gettysburg2, for example, stresses the railroad and logistical systems that existed in the American Civil War.

Brewer & Shubik, p. 22

A second mention of commercial hobby wargames appears in The War Game in a discussion of Gaming for Entertainment:

We include amateur war gaming in the category of participant sports. The subscription list for The General, the house publication of the Avalon Hill Company of Baltimore, is somewhere around 20,000. Simulations Publications of New York lists about 30,000 subscribers to its general magazine, Strategy and Tactics, and some 7,000 subscribers to its more detailed, game-oriented Moves. Thus, even assuming some overlap, the number of serious amateur war gamers in the United States in 1976 was about 40,000. This population is considerably larger than that of professional war gamers. Some of the planning factors used in amateur war gaming may even be more accurate than those used by professionals; at least the data are more openly available and are actively challenged by this large and active group of amateurs. SINAI3 and MECH-WAR ’774, two recent, innovative Simulations Publications games, indicate just how realistic an amateur war game can be.

Brewer & Shubik, p. 39

As we know from other contemporary accounts from wargame practitioners in those days, like those found in Jim Dunnigan’s Wargames Handbook, Third Edition (Writers Club Press, 2000 but first printed in 1980) or Dr. Peter Perla’s The Art of Wargaming (Naval Institute Press, 1990) that hobby wargamers indeed played a major role in the wargame practitioners community much like they continue to do so today. It is a shame The War Game fails to reflect their contributions.

Enhancing from the past

As I wrote in an May 2023 blog post for the Armchair Dragoons titled, “Enhanced DoD Wargaming According to GAO and Relevance to Hobby Wargaming,” the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reviewed the Department of Defense (DOD) use of analytic wargames. The GAO report examined: (1) the scope of DOD’s wargaming activities; (2) DOD’s use of internal and external wargame providers; and (3) the extent to which DOD ensures wargame quality. As I commented back in April, the GAO wargaming report focused on providers of wargames which it identified as a mix of organizations internal to the DoD, federally-funded research & development centers (FFRDC), and contractors. As the GAO report highlighted, “The mix of wargame providers used across DOD varies and comes with advantages and disadvantages including varying capacity, timeliness, information access, expertise, and independence.” The GAO commented that the DoD never assessed the use of this variety of wargame providers and therefore resources for wargaming were misaligned. The report noted, “While DOD organizations conducting wargames use no single quality framework, the frameworks used by DOD organizations share common quality principles.” The 13 common principles identified by the GAO were divided into three broad areas: Wargame design and development, Wargame conduct, and Wargame documentation and analysis.

It will likely surprise no one that The War Game had broadly similar recommendations, likewise divided into three broad categories: Improving Standards, Improving Stewardship, and Improving Performance. Readers of The War Game will almost certainly find direct or indirect connections between the three broad areas of recommendations in The War Game and the 13 common principles in the GAO report published over 40 years later.

C’mon, DOD, you gotta do better.

Note: While I acquired a dead-tree version of The War Game, a digital version is available at https://archive.org/details/wargamecritiqueo0000brew/page/n7/mode/2up.

- Dupuy, T.N. (1979) Numbers, Predictions & War: Using History to Evaluate Combat Factors and Predict the Outcome of Battles. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill. ↩︎

- Uhl, Mike (1979) Gettysburg. The Avalon Hill Game Co. ↩︎

- Dunnigan, Jim (1973) Sinai: The Arab-Israeli Wars -’56, ’67, ’73. New York: Simulations Publications, Inc. ↩︎

- Dunnigan, Jim (1977) MechWar ’77: Tactical Armored Combat in the 1970s. New York: Simulations Publications, Inc. ↩︎

Feature image courtesy RMN

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2025 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0