In the forward to Algorithms of Armageddon1, Robert O. Work explain how the book attempts to “explain AI [artificial intelligence] in a way that any interested person can absorb in order to understand its impact on national security” (Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. ix). In a refreshing bit of honesty, Work goes on to explain that they don’t necessarily agree with all authors Galdorisi and Tangredi write:

That is not to say that I agree with every one of their conclusions. But I am full agreement with their concern that the true danger is not on of AI controlling humans, but of humans using AI to control other humans. That is the concern that prompted their writing of the book. Like them, I don’t want to see the United States ever controlled by the algorithmic capability of an opponent.

Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. ix

While there is much to digest in Algorithms of Armageddon, one section in particular resonated with the hobby gamer in me. From it I take hope that even a simple game, like Fluxx, may be our best hope to keep AI in check.

Doubt in war

In Chapter 10 of Algorithms of Armageddon, Galdorisi and Tangredi discuss the Fog of War which they define as doubt and incomplete information. The point out that, “Doubt is a human ability that, as of today, AI systems have not yet demonstrated” (Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. 168). They go on to point out that machine AI excels at the OODA loop [Observe-Orient-Decide-Act] but in a human the loop is better described as OODDA as in Observe-Orient-Decide-DOUBT-Act (Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. 168).

In Algorithms of Armageddon Galdorisi and Tangredi talk about how AI is supposed to lift the fog of war (what others like Antal and Watling call “The Transparent Battlefield”). The problem, however, is doubt that comes from imperfect information:

Can AI systems operate effectively with limited access to information? Is there a point at which information is so limited that a human—able to accept the reality of the fog and doubt one own’s plan—is more effective at correlating and understanding the available information than AI?

Galdorisi & Tangredi, pp. 168-169

Galdorisi and Tangredi point to big AI such as Deep Blue or IBM’s Watson that, “operate under the assumption of open access to large amounts of information—in other words, free big data.” They continue, “[AI systems] have operated under conditions of complete information. All the rules of the game are known. There are no changes to the rules during competition” (Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. 169).

Galdorisi and Tangredi go on: ” The AI is trained to learn and know every possible move. The point of utilizing AI is to determine all the possibilities of gaming move after move, thousands, perhaps millions, of times, until every possible combination (allowed under the rules) is identified and, in effect, practiced” (Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. 169).

The authors then raise the question, “However, what happens when the rules change in the middle of the game? Can the algorithm adapt?” They continue:

Or, more complex still, what if the human player suddenly pulls a checkerboard out in the middle of the chess game? The AI machine as never played checkers. It is not trained to calculate all possible checker combinations; it doesn’t even recognize the game. It now faces an environment of incomplete information. A human playing another human could likely adapt to checkers since it is a well known human game. The human can respond to the unexpected move.

As of today, no one has built and AI system that can do that.

Galdorisi & Tangredi, p. 169

Rules in Fluxx

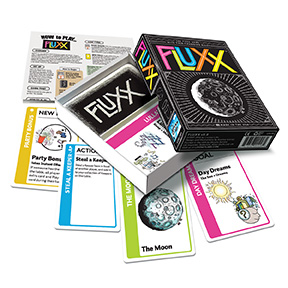

Which brings me to Fluxx from Looney Labs:

It all begins with one basic rule: Draw one card, Play one card. You start with a hand of three cards… add the card you drew to your hand, and then choose one card to play, following the directions written on your chosen card. As cards are drawn and played from the deck, the rules of the game change from how many cards are drawn, played or even how many cards you can hold at the end of your turn.

Not only do the rules of the game change, so can the goals (victory objectives):

Even the object of the game will often change as you play, as players swap out one Goal card for another. Can you achieve World Peace before someone changes the goal to Bread and Chocolate?

Fluxx ad copy

If Galdorisi and Tangredi are right, games like Fluxx could be the ultimate AI breaker. Does that make Algorithms of Armageddon really Algorithms of BoardGameGeek? Hardly, but it is something to ponder.

Recommended.

- Galdorisi, G. and S. J. Tangredi (2024) Algorithms of Armageddon: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Future Wars. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ↩︎

Feature image automatically generated using WordPress AI based on text of post.

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2024 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ![]()

That is an interesting thought about Fluxx.

I have seen people not being able to play Fluxx, as they were thrown off by the constant ruleschange. And other people thrive on it, as they can, and did, work with the shifting play environment. So humans can also be stymied by uncertainty, but then they just choose to not play. I’m not certain an AI can do that.

Hi Rocky,

cheers for the book recommendation – I didn’t know about this one.

I need to find the time to write back to you on your comments re Watling’s book. In the meantime, and linking to your thoughts here, it is worth keeping in mind that there is usually a huge difference between demonstrating a piece of technology in a controlled environment and doing so in a completely uncontrolled or contested environment (e. g. as in an adversary influencing that environment in subtle and important ways).

Watling does comment on that, but I guess that the hype is too strong and folks’ imagination is captured by big ticket demonstration of prototypes, rather than by the day-to-day grind of scientific research and practical engineering.

Remember that “Go was a solved problem”? Well, guess what, not quite

https://arstechnica.com/ai/2024/07/superhuman-go-ais-still-have-trouble-defending-against-these-simple-exploits/

It is important to note the choice of words – it is not an innocent one. Labelling strategies like the above as “exploits” places the shortcomings as something “unfair”, “rare”, “tricky”, etc. This is pretty much the same strategy as with self-driving car accidents: place the “blame” firmly on the hands of God or Nature and then carefully walk back from the hype while making sure that you have something new (or apparently new) to hype up.

Eventually “self-driving cars” become more like drones which are supervised by “traffic controllers”. More realistic but way way less exciting and fun that “self-driving cars”, “self-playing games”, etc. etc.