On 8 June 1982 one of the more interesting air strikes of the Falklands War took place. On that day, an Argentine Air Force C-130 Hercules transport bombed Hercules, a Liberian-flagged very large crude carrier (VLCC). In the first year after the war the attack got barely a mention in English-language books. Take, for example, this passage from the Osprey Publishing Men-at-Arms Series book Battle for the Falklands (3) Air Forces published in 1982:

The Argentines had in the meantime adopted desperate methods in their efforts to bomb shipping: on 31 May a C-130 made a bombing attack on a British tanker well north of the TEZ [Total Exclusion Zone], the bombs being pushed off the rear loading ramp. One struck the ship, but bounced off to no effect. (A game but foolish attempt to repeat this technique the next day is thought to have been behind the C-130 kill by a Sea Harrier described earlier.) On 8 June the US-leased tanker Hercules received two unsuccessful attacks from a C-130, following a radio message to divert to an Argentine port.

Braybook, R. (1982). Battle for the Falklands (3) Air Forces. Osprey Publishing. p. 27

As a later U.S. Supreme Court proceeding (U.S. Reports: Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp. et al., 488 U.S. 428 (1989)) fuller, and much more interesting, details were released:

Amerada Hess used the Hercules to transport crude oil from the southern terminus of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in Valdez, Alaska, around Cape Horn in South America, to the Hess refinery in the United States Virgin Islands. On May 25, 1982, the Hercules began a return voyage, without cargo but fully fueled, from the Virgin Islands to Alaska. At that time, Great Britain and petitioner Argentine Republic were at war over an archipelago of some 200 islands—the Falkland Islands to the British, and the Islas Malvinas to the Argentineans—in the South Atlantic off the Argentine coast. On June 3, United States officials informed the two belligerents of the location of United States vessels and Liberian tankers owned by United States interests then traversing the South Atlantic, including the Hercules, to avoid any attacks on neutral shipping.

By June 8, 1982, after a stop in Brazil, the Hercules was in international waters about 600 nautical miles from Argentina and 500 miles from the Falklands; she was outside the “war zones” designated by Britain and Argentina. At 12:15 Greenwich mean time, the ship’s master made a routine report by radio to Argentine officials, providing the ship’s U.S. name, international call sign, registry, position, course, speed, and voyage description. About 45 minutes later, an Argentine military aircraft began to circle the Hercules. The ship’s master repeated his earlier message by radio to Argentine officials, who acknowledged receiving it. Six minutes later, without provocation, another Argentine military plane began to bomb the Hercules; the master immediately hoisted a white flag. A second bombing soon followed, and a third attack came about two hours later, when an Argentine jet struck the ship with an air-to-surface rocket. Disabled but not destroyed, the Hercules reversed course and sailed to Rio de Janeiro, the nearest safe port. At Rio de Janeiro, respondent United Carriers determined that the ship had suffered extensive deck and hull damage, and that an undetonated bomb remained lodged in her No. 2 tank. After an investigation by the Brazilian Navy, United Carriers decided that it would be too hazardous to remove the undetonated bomb, and on July 20, 1982, the Hercules was scuttled 250 miles off the Brazilian coast.

While that is the legal U.S. version, at least one British commentator on the Falklands War pokes fun at Argentinian conspiracies: “Eventually, the VLCC Hercules will be left to sink, being too dangerous to repair. Despite being a neutral vessel, unconnected with the war, she remains the largest ship ever sunk by aircraft since WW2 and possibly even including it. Argentina now pretends she was a British ship!”

An Argentine website explains the different interpretations. I highlight here some key excerpts (below text is machine-translated using DuckDuckGo):

Activities on June 7th:

- 12.45: a Boeing B – 707 aircraft, registration TC – 92 with the indicative “Ship 2”, who performed tasks of exploration and distant reconnaissance reports that in the assigned search area he observes, among others, a large cargo ship, in the coordinates 42º13´ S 48º 16´ W, heading 200º/210º and at a speed of 16/18 knots, defeat that led directly to the concentration area of the enemy fleet. (Summary of the FAS)

- 15.10: the FAS requires the ARA to provide information about that ship and others.

- 19.10: A 3 of the ARA Command is informed that Ship 2 detected at 12.30 a large ECO [Enemy Combatant?] (possibly frigate) in 47 20′ S and 36 20′ W at a speed of 17 Kts. and a large freighter at 12.45 at coordinates 42º13´ S 48º 16´ W, with the course and speed mentioned above.

- That response was interpreted as saying that the Navy was unaware of the movement of the large ship, therefore a stricter control over the ship was ordered, given the possibility that it would supply the enemy fleet.

Activities on June 8th:

- 09.55: Immediately, armed with the bomb system, the first attack is executed (launch of six bombs) observing in the turn that some bombs exploded at the height of the waterline and close to the bow and others in the water at 50/60 meters long. (Report after the flight)

June 12

- The Hercules anchors two miles from Ilha Rasa, near Rio de Janeiro. It has two small holes of 50/60 centimeters in diameter and a slight inclination, which is almost imperceptible.

June 17

- The company Cardozo y Fonseca (representatives of the company that owns the ship in Brazil) reports that it has hired a team of experts from the USA to disarm the bomb.

- The 1000-pound pump is in warehouse number 2.

July 11

- Cardoso and Fonseca informs that further investigations will be necessary to prepare for the deactivation. Experts consider it impossible to deactivate the bomb. It is decided to sink the ship, explaining that the insurer has decided that it is better to pay the price of the ship than the risks that are taken if something goes wrong.

In summary the Argentine website notes:

The unknowns about what happened with the VLCC Hercules are the following:

- A ship of that size and autonomy made a technical stopover in Rio de Janeiro with the costs that this implied and what was not usual.

- After the attack he sailed 2000 km in all kinds of weather conditions without problems, despite having an unexploded 1000-pound bomb, then it was decided that it was dangerous to deactivate the bomb and it was decided to sink it.

- Once they arrived at port, the crew were sent to their country of origin, except for the captain.

- The owners rejected the purchase proposals of several international firms, which wanted it even as junk.

- Few people got on board, for security reasons.

- The people who boarded when the ship was in port did not take any photos of the inside of the ship or the bomb in question.

So what does this have to do with wargaming?

If wargamers want to recreate this “battle” they can now download a free wargame from Long Face Games available on WargameVault. Designed and illustrated by David Manley, a long-time naval wargame designer, TC-68 Mission of Glory! – A Solitaire 5 Minute Wargame is there for your enjoyment.

This one page print-n-(quickly) play wargame takes longer to print than it does to play. As the ad-text of the game declares:

It is the closing days of the Falklands Conflict. 8th June 1982. Recreate the FAA’s glorious attack on the tanker Hercules, clearly carrying supplies for the Brits and definitely NOT a neutral tanker at all. You only have a few bombs so you have up to three chances to send the Gringo to the bottom. Good luck!

Uh…ok.

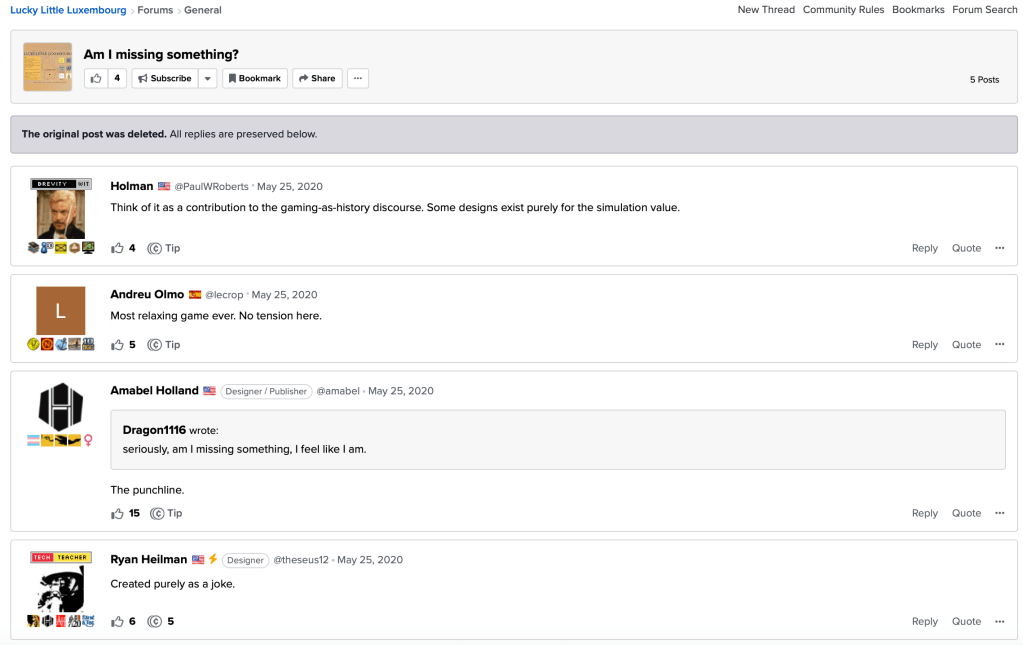

To be clear, TC-68 is in the same category of wargaming as Lucky Little Luxembourg (Ryan Heilman, web-published, 2020). If you haven’t already figured it out this is not a serious wargame.

Which is a bit sad. The situation presented, a military transport aircraft hastily converted into a bomber striking a very large commercial ship, would be interesting to play out. One could even throw in some roleplaying game elements here. I am actually quite surprised that I see few references connecting Hercules to Liparus from the 1977 James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me:

I mean, there are many alternate gaming scenarios possible:

Feature image courtesy @FirstFlklands via X

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2024 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ![]()