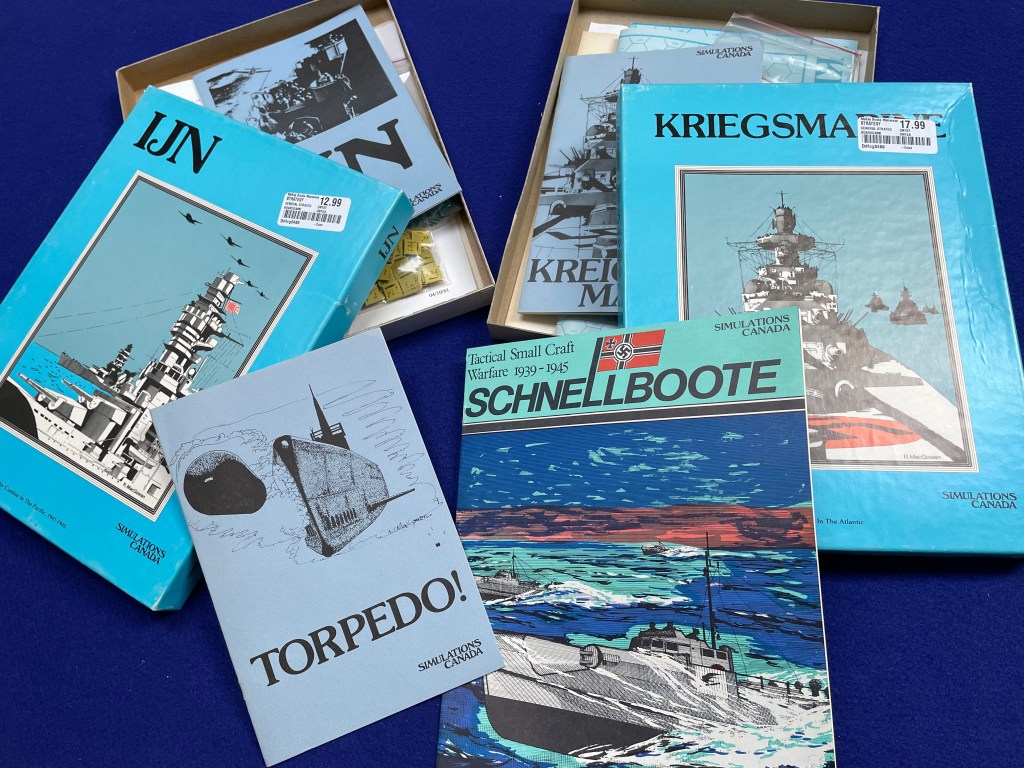

I just happened to be visiting the local used bookstore and came across two games that I had heard about many years ago but had not acquired. I quickly rectified that situation and went home in a happy mood. The two games are both part of a series of games by designer Stephen Newberg and published by Simulations Canada between 1978 and 1980.

Opening the two games, however, revealed additional content.

A bit to my surprise, what had come into my possession was the complete four-game series of Simulations Canada’s World War II tactical naval combat wargames by designer Stephen Newberg. The four games (in order of publication) are:

- IJN: A Tactical Game of Naval and Naval-Air Combat in the Pacific, 1941-1945 (SimCan, 1978).

- Torpedo! A Game of Tactical Submarine and Anti-Submarine Combat During the Second World War (SimCan, 1979).

- Kriegsmarine: A Tactical Game of Naval and Naval-Air Combat in The Atlantic and The Mediterranean, 1939-1945 (SimCan, 1980).

- Schnellboote: Tactical Small Craft Warfare 1939-1945 (SimCan, 1984).

Geek feels

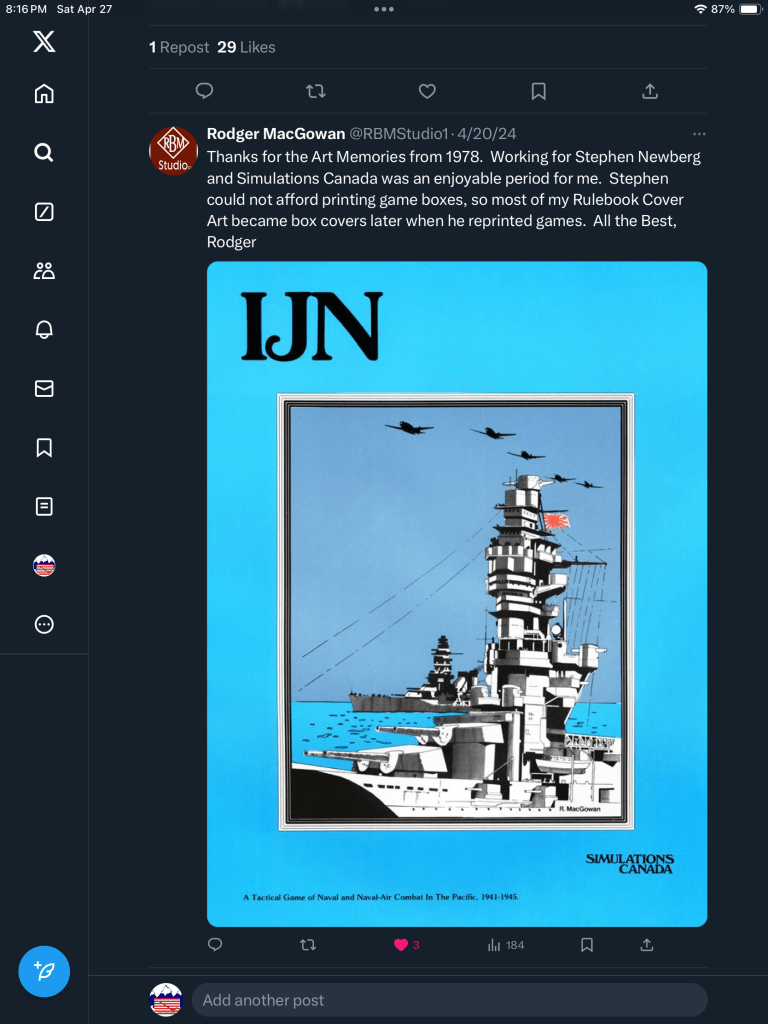

There are some in our hobby who absolutely love to denigrate wargames from the 1970’s and 1980’s, especially if they use hex & counter. From that perspective, Newberg’s SimCan tactical naval games should be consigned to the dustbin of history (those who denigrate would, if they were totally honest, tell us they prefer a dumpster fire). Even I admit that in terms of production value these games are nothing to write home about. The rule books have very much that early desktop publishing feel, the counters are small and in unexciting pastel colors with lots of numbers but no fancy graphics. The map sheets are very generic and so, so plain. Unfortunately, over 40 years later it is easy to forget that for many designers and publishers making a game was a labor of love that often meant pinching pennies.

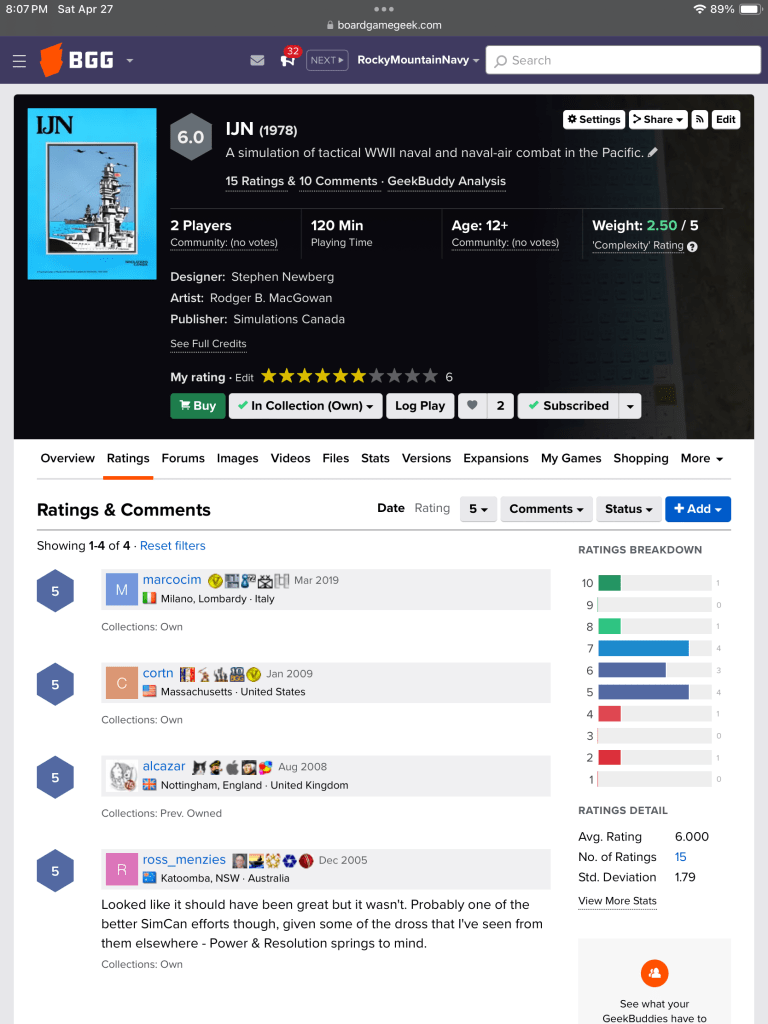

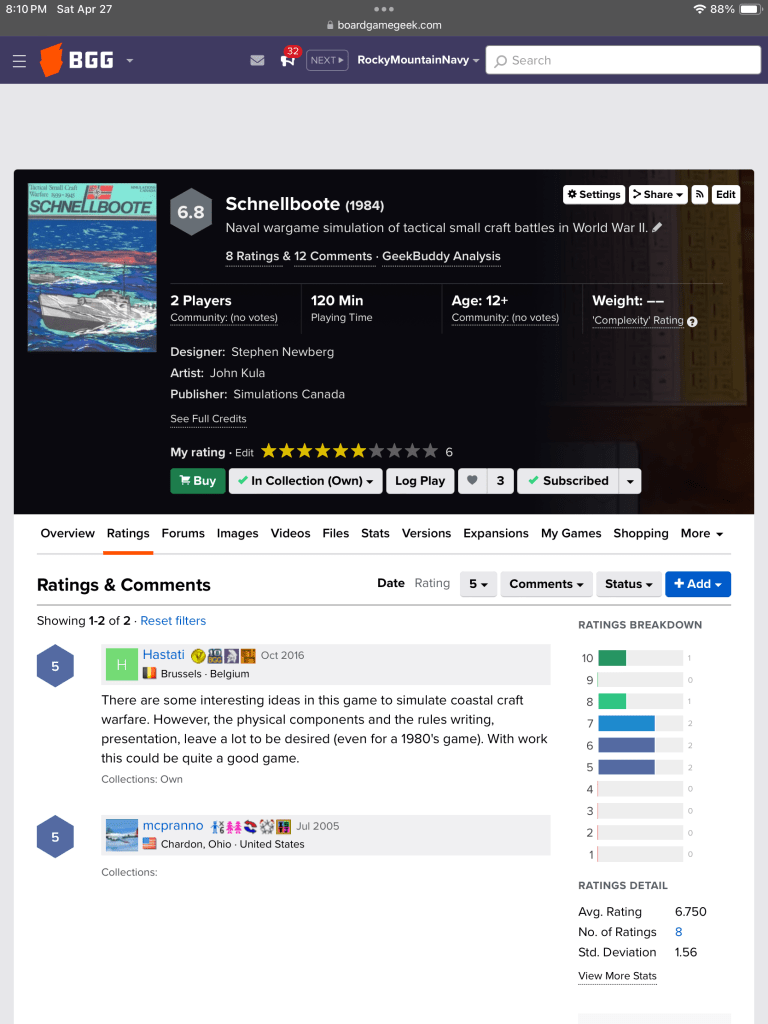

Looking at the ratings for these games on BoardGameGeek also shows more than a few less-than-flattering comments:

But then you get ratings like this, submitted just over a year ago by none other than distinguished game designer Mark Herman who has designed wargames and boardgames for decades:

What does Mark Herman see in this series that others, even myself, apparently don’t? To answer that question I dug into the four games. That deep dive lead to my discovery of a very playable game design that makes sense once you understand the designer’s intentions was not to make the ultimate tactical naval combat wargame.

Not dying on that (Avalon) Hill

The design lineage of the series is interesting. Writing in the Designer’s Notes for IJN, Stephen Newberg relates:

I.J.N. has a rather mixed genesis. The game system was first begun as a project for Avalon Hill. In that incarnation it was designed to represent WWII submarine and anti-submarine operations. When the project fell through the system was shelved. It began it’s second life as a search for some 2400th miniatures rules for use at a Sunday game session. I remembered that one of the more enjoyable scenarios that we had play tested in the systems first life had been primarily a surface naval action that a submarine just happened to be in the vicinity of. A little experimenting led to the determination that the system was a good base for surface actions as well as subsurface ones.

IJN 16.0 Designer’s Notes

The game had one not-so-small problem; it was too large to publish coming in at over 60 pages of rules, 175 scenarios, and in excess of 600 counters (which eventually grew to 750). Newberg decided to divide their work into three “mateable” games sharing a common rules set and data base. This was the birth of IJN, Torpedo!, and Kriegsmarine (IJN, 16.0, Torpedo! 18.0). The fourth game in the series, Schnellboote, was revealed in the Designer’s Notes for Kriegsmarine (Kreigsmarine 16.0).

Knife-fight at sea

Newberg’s WWII tactical naval games all share the same scale; 90 seconds per turn and 100 yards per hex (IJN 3.5 Scale). Naval grognards may recognize that this scale is unusually small, a point Newberg addresses in the Designer’s Notes for Kriegsmarine:

Kriegsmarine itself and the entire series of games in which it is a member, were designed from a somewhat unusual viewpoint for a naval simulation in that they concentrated on very close range actions and the results of such actions. Most naval games tend to have scales using hexes of 1000 yards or more compared to the 100 yds of this series. Time was likewise taken in short increments of 90 seconds instead of the the more normal 6 minutes. The reasoning behind this was to show only short range effects which had previously been somewhat ignored. There are no long range gun battles in the IJN, Torpedo!, Kriegsmarine system. Instead the more common, and usually much more vicious, short range stumble on the enemy, shoot, and then he is gone type of action comes to the fore.

Kriegsmarine, 16.0 Designer’s Notes

Newberg’s “knife fight in a phone booth” design is further explained in the Design Notes for Schnellboote:

The system portrays the close quarters skirmish. It is the more common, and often vicious, short range stumble upon the enemy that we were after. Gunfire trajectories are flat at such ranges and penetration the main concern. Hence the gunfire table mainly determines if you get through the armor. When that happens you go directly to a damage table that is broken down to reflect the historical types and levels of damage taken by various ship types when penetration occurred. Very high movement allowances, due to the scale, accurately reflect the difficulty of pinning down a target at these kind of ranges as well as giving a very realistic subjective feel of fast vessels racing past each other while slashing away in the darkness.

Schnellboote, 15.0 Design Notes

Formation course

As promised, the four games of Newberg’s World War II tactical naval wargames share a remarkably similar, though not strictly identical, rules structure.

| IJN | Torpedo! | Kriegsmarine | Schnellboote |

| 1.0 Introduction | Introduction | Introduction | Introduction |

| 2.0 General Course of Play | General Course of Play | General Course of Play | General Course of Play |

| 3.0 Game Equipment | Game Equipment | Game Equipment | Game Equipment |

| 4.0 Sequence of Play | Sequence of Play | Sequence of Play | Sequence of Play |

| 5.0 Search | Search | Search | Search |

| 6.0 Gunfire Combat | Gunfire Combat | Gunfire Combat | Gunfire Combat |

| 7.0 Vessel Movement | Submarine Depth Change | Vessel Movement and Depth Charge Combat | Vessel Movement |

| 8.0 Aircraft Movement, Bomb Combat, and Air to Air Combat | Surface Vessel Movement and Depth Charge Combat | Aircraft Movement, Bomb Combat, and Air to Air Combat | Torpedoes |

| 9.0 Torpedo Launching, Movement, and Combat | Aircraft Movement, Bomb Combat, and Air to Air Combat | Torpedo Launching, Movement, and Combat | Speed Change |

| 10.0 Acceleration and Deceleration | Torpedo Launching, Movement, and Combat | Acceleration and Deceleration | Facing |

| 11.0 Facing | Submarine Movement | Facing | Stacking |

| 12.0 Stacking | Acceleration and Deceleration | Stacking | Victory Conditions and Game Set Up |

| 13.0 Victory Conditions and Game Set Up | Facing | Victory Conditions and Game Set Up | Optional Rules |

| 14.0 Optional Rules | Stacking | Optional Rules | Scenarios |

| 15.0 Scenarios | Victory Conditions and Game Set Up | Scenarios | Design Notes |

| 16.0 Designer’s Notes | Optional Rules | Designer’s Notes | Charts, Tables, and Examples |

| 17.0 Charts and Tables | Scenarios | Charts and Tables | |

| 18.0 Designer’s Notes | |||

| 19.0 Charts and Tables |

The similarity in rules structure carries over into the General Course of Play which is repeated across all four games with only a slight variation between each:

In each scenario each player will be cast in the role of the commander of a submarine, vessel or aircraft, or a group of the same. Historic forces and their dispositions will be detailed by the scenario. Then, following the rules outlined below, each player will attempt to destroy the opposing player by search, maneuver, and attack, in such a way as to satisfy the victory conditions and in so doing, win the game.

Torpedo!, 2.0 General Course of Play

The Newberg Method

Understanding Newberg’s design approach is crucial to appreciating the rules of the series. Newberg makes some significant design decisions in the rules and, if one does not understand the designer’s intent, those rules will very likely be challenging to grok not only for how they are presented but for what they are portraying.

Seek…

The first major design decision Newberg makes regards search, an issue they address head-on in the Designer’s Notes for the first game in the series:

Since the search system came up lets stop on it for a moment. It is a bit of a hassle to use and requires a bit of paper work. Of course, on a game of this scale some paper work is usually required. But the search system is the heart of the night actions. It provides the fog of war that is nowhere more evident than at sea in the dark. As a player, it puts you right into that murky uncertainty. The system is also central to the submarine actions of Torpedo! where it hides hunter and prey, leaving much confusion as to which might be which.

IJN, 16.0 Designer’s Notes

Take particular note of the sentence, “The search system is the heart of the night actions.” When reading the rules for IJN, Kriegsmarine, and Schnellboote it is not until the end of rule 5.0 SEARCH / 5.1 General that we read, “For daytime scenarios the search phase is suspended. All units remain on the map at all times and are always considered to be sighted by opposing units.” Significantly, this daylight rule exception is deleted in Torpedo! which forces all units to conduct a search phase each turn. That extra demand is offset to a degree by the rule across the series that states, “Once a unit is sighted it is considered to be sighted by all opposing units and no further searches for it need be conducted that turn” (5.2 Procedure). As we will see in a moment, that rule was not Newberg’s but one demanded by playtesters. For daylight scenarios without submarines, Newberg very obviously wants the scenarios to focus on the battle engagements and less on pre-battle maneuvering of forces as they approach combat ranges.

In the Designer’s Notes for Torpedo! Newberg explains their view of combat came down to “days of utter boredom between minutes of total activity.” This in turn lead some design objectives:

An immediate objective of the design was to eliminate the days of boredom while preserving the action and retaining realism. The search system and the starting point for the scenarios were the outgrowth of this desire. Scenarios start at a point where the submarine has moved into a position to begin an attack procedure. The search system simulates the problem experienced by all submarines — and, indeed by all other units — that of maintaining a contact for the attack while remaining undetected.

Players must continually chose either to increase their ability to detect or to decrease the likelihood of being detected. To simulate the limited degree of intelligence appropriate to a WWII submarine situation, unit status sheets are used to keep track of the action of units, thus forcing only those units which have been signed [sic] to perform their actions visually. This sheet was also a convenient method of handling supply records, which are required in a simulation on this scale.

The rule which allows a unit to be sighted by all opposing units once sighted by one was a concession to the playtesters. The rule saves time and paperwork that badly damaged playability; and it makes sense since most units would sight a submarine if told where to look. People who demand complete realism should change this rules and have each unit perform search every turn, and keep track of units which have sighted which other units. Be warned: It’s a lot of work.

Torpedo!, 18.0 Designer’s Notes

Newberg’s search mechanism is to compare a search value (radar, sonar, or visual) to the Aspect value of the target. The difference is the column to be used on the SIGHTING TABLE to determine if the target is sighted or not. Night lighting conditions (Moonlit or Dark) are depicted by shifting columns. Optional rules introduce additional modifiers for quality of personnel and weather.

…and destroy

Given Newberg’s series takes place during World War II there are rules for Gunfire Combat, Depth Charge Combat, Aircraft Bomb Combat, Air to Air Combat, and Torpedo Combat. Each uses a similar “superiority” game resolution mechanism where an attack value is compared to the relevant defense value with the differential used to determine which column on the appropriate combat table is rolled against to determine if a hit is scored (Gunfire, Bomb, and Air to Air) or the damage inflicted (Depth Charge and Torpedo). While each share a common approach to the rules for resolving combat, each also has individual nuances.

Gunslingers

As already discussed, Newberg’s design emphasis is on “the close quarters skirmish” (Schnellboote, 15.0 Design Notes). Newberg tells us in the Designer’s Notes for Kriegsmarine this is by design: “There are no long range gunbattles in the IJN, Torpedo!, Kriegsmarine system” (Kriegsmarine 16.0 Designer’s Notes). Recall Newberg’s explanation of gunnery:

Gunfire trajectories are flat at such ranges and penetration is the main concern. Hence the gunfire table mainly determines if you get through the armor. When that happens you go directly to a damage table that is broken down to reflect the historical types and levels of damage taken by various ship types when penetration occurred.

Schnellboote, 15.0 Design Note

Gunfire Combat is found in rule 6.0 GUNFIRE throughout the series. After calculating the superiority differential and determining if a hit is made, a second roll is made on the DAMAGE INCURRED TABLE.

Rule 6.3 SPLITTING GUNFIRE is most assuredly one that will offend modern day wargame players. In an effort to create a bit of some realism without resorting to having too many factors on an already small counter, the rule provides for “splitting” the gunfire factor between primary and secondary guns and targets in bow/stern area or port/starboard areas. Here even I will admit the rule could be better written, perhaps with a few more sub bullets. Contemporary wargames would almost certainly have a graphic on a player aid explaining this rule. This in turn raises a tangetial point; the fact Newberg’s design lacks the “bling factor” should not be a criticism and I always hope contemporary players can recognize that some designs are “of their time” but, alas, all too often I come away from such conversations disappointed.

For wargamers who are obsessed with naval gunnery, the range rule (IJN / Torpedo! / Kriegsmarine 6.4.4, Schnellboote 6.43) will likely offend them. Here is the Torpedo! version that covers surface ships, submarines and aircraft:

Range affects gun strength. Strengths for vessels and submarines are normal at ranges of 0-20 hexes, halved at 21-40 hexes, and quartered at over 40 hexes. Drop all fractions. For Aircraft strengths are normal at ranges 0 to 10 hexes, halved at 11 to 20 hexes, quartered at 21 to 40 hexes and dropped to zero at over 40 hexes.

Torpedo!, 6.4.4

Thematically, if one is using a salvo fire model (each shot is a salvo of guns where the next salvo is not fired until the previous impacts) then this rule makes sense in that the strength of gunfire falls off as range increases, in no small part because the time of flight for a salvo takes longer at greater ranges and thus less iron is moving downrange. Realistically, the range breaks make little sense; a range of 40 hexes is 4000 yards or a mere two nautical miles. The main gun on U.S. Navy destroyers in World War II, the 5″/38 Mk 12, had a maximum range of 18,200 yards—9.1 nautical miles or 182 hexes (NavWeaps.com 5″/38 (12.7 cm) Mark 12).

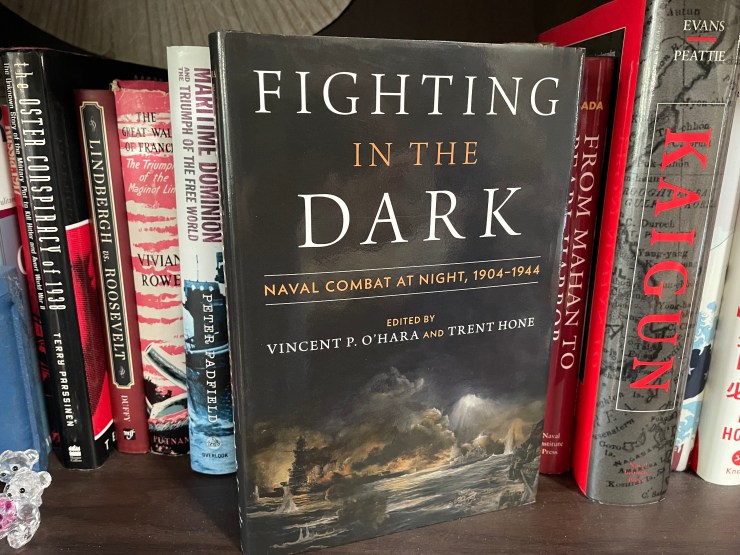

Based on historic gun battles at night in World War II, Newberg seems to have shortened the range of battle by half. As naval historian Jonathan Parshall points out in his chapter “How Can They Be That Good? Japan, 1922-1942” in Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night: 1904-1944, the primary gunnery action at the Battle of Savo Island (8-9 Aug 1942) took place at a range of about 6,200 meters (~6,780 yards) or within 62 hexes. At the Battle of Cape Esperance USS Helena opened fire at a range of 5,000 yards (50 hexes). At the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal “the Americans basically speared themselves into the middle of Abe’s formation…It was, in the words of one American skipper, ‘A barroom brawl after the lights had been shot out’.” At the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, USS Washington opened fire at a range of 8,400 yards [84 hexes]—”not ‘point blank,’ as it is often described in accounts of the action, but definitely within what one of Washington’s officers described as ‘body-punching range'” (O’Hara, V. P., & Hone, T. (2023). Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night: 1904-1944. Naval Institute Press. pp. 165-176).

Newberg’s design, however, seems to focus on battles within 40 hexes. Though unstated by the designer, I suspect this was another concession to playtesters and a design decision perhaps driven by the components. The mapsheet in IJN is roughly 48 x 34 hexes (4,800 yards by 3,400 yards) using an already small 5/8″ hex—barely big enough to fit the half-inch counters. This apparent design decision has all the hallmarks of a recognition of playability within the limits of available components over realism by the designer…and it works.

Going deep: depth charge combat

Like gunnery combat, the rules for depth charge combat also reflect playability over strict realism. When making an attack against a sighted submarine (i.e. a submerged submarine that is detected via sonar) the usual superiority combat mechanism is used with the DEPTH CHARGE SUPERIORITY table. Against an unsighted submarine, i.e. one that was maybe previously sighted but is not presently, it is still can be attacked though the maximum damage (assuming the attacker designates the right hex the submarine is hidden in) is that that submarine cannot fire torpedoes in the following Torpedo Launching, Movement, and Combat Phase.

In some ways anti-submarine warfare is akin to knife-fighting with blindfolds where you have to depend on senses other than sight to guide your attacks. Newberg’s games can be used to make a credible recreation of iconic small-ship anti-submarine warfare battles. Take for instance the battle of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Spencer (WPG-36) and German submarine U-175 on 17 April 1943:

The weather was fair and seas were calm on 17 April, but the day began with a shock as U-628 torpedoed the British merchant ship Fort Rampart. Commander Berdine piloted the Spencer to screen the Canadian corvette HMCS Arvida as she picked up survivors. The Spencer then maneuvered to rejoin the convoy. As she closed, the sonar operators picked up another contact at a range of about 1,500 yards. Berdine hurried back to the bridge and ordered full speed ahead to investigate.

Less than a mile away and about 50 feet below, U-175 was stalking the tanker G. Harrison Smith. The submarine was at periscope depth, and Kapitänleutnant Bruns was assessing the target through the scope. He was eager to attack, blessing his luck that the convoy had come right to him, while his executive officer and crew were somewhat anxious about his decision to engage in broad daylight. Then his hydrophone operators heard a rapidly approaching warship, followed shortly by the unmistakable sound of active sonar pinging off their hull. Suddenly faced with an incoming Treasury-class cutter filling his periscope, Bruns briefly considered firing torpedoes but instead ordered immediate evasive action; U-175 dove deeper while turning to starboard.

Berdine figured the sub would come right to evade. He immediately ordered a spread of 11 depth charges as the Spencer steamed over the U-boat’s estimated position. The round canisters dropped and sank to a preset depth before exploding.

Below, the crew of U-175 heard the cutter pass overhead, and then the depth charges began detonating beneath them. Energy travels much more efficiently in water than in air; the force generated by hundreds of pounds of high explosives violently rocked the submarine and her crew. The damage was substantial and included forward flooding, disabled bilge pumps, dislocated engines, and broken gauges. The hull was warped so severely that the watertight doors could not be closed

….

Meanwhile, the Spencer was still tracking her quarry. A column of the convoy’s merchant ships was getting uncomfortably near; they were within easy torpedo range if the U-boat was still operational. Berdine ordered another spread of 11 depth charges—this time set to explode deeper—and then a volley of mousetrap rockets. The deadly canisters again dropped from the Spencer and blew spectacular explosions of water in the wake.

The cutter’s second depth charge barrage was dead-on. U-175 was rocked again by underwater blasts, this time rupturing the pressure hull, damaging electric motors, breaking open battery containers, and activating two torpedoes in their tubes. The U-boat was flooding now, filling with toxic gas from the batteries, and two of her torpedoes were possibly about to explode. To remain submerged was certain death; the engineer officer, Oberleutnant Nowroth, ordered ballast tanks blown for an emergency ascent. Bruns ordered the two torpedoes jettisoned and concurred with preparations to abandon ship.

U-175 suddenly surfaced about 2,500 yards from the Spencer. When a U-boat popped up in close proximity, it was critical to stop her crew from manning the deck guns to engage the escorts. The Spencer immediately opened fire with any weapons that would bear, joined shortly by the Duane and naval guards on nearby merchant ships. They scored several hits, mostly on the U-boat’s prominent conning tower. But some of the rounds fired from the merchant ships hit the Spencer, causing multiple casualties. Berdine ordered flank speed and prepared to ram as his gun crews kept pouring fire at the U-boat.

“A Nautical Knife Fight,” Naval History Magazine, April 2024

In game terms, on turn 1 Spencer detects submarine U-175 at periscope depth and closes rapidly. U-175 fails to detect Spencer. On turn 2:

- Search Phase: Both Spencer and U-175 sight each other.

- Submarine Depth Change Phase: U-175 goes from periscope depth to shallow.

- Vessel Movement and Depth Charge Phase: Spencer drops a pattern of depth charges. As U-175 is still sighted the DC attack procedure in Torpedo! 8.3.1 is used. Assuming Spencer has a DC factor of 2 and U-175 has a DC defense of 1 we roll on the DEPTH CHARGE COMBAT TABLE on the 1 column for Spencer’s superiority number. The damage roll was likely a [1] for 4F—at 7F submerged submarines must surface.

On turn 3 Spencer conducts a second attack against U-175 which is now at deep depth. The DC attack scores at least 3F damage which forces U-175 to the surface. On turn 4 Spencer and other ships of the convoy take the now surfaced U-175 under fire in the Gunfire Phase of the turn.

Airing out the design

There are four types of aerial combat in Newberg’s quartet of tactical naval combat games: level bombing, dive bombing, torpedo bombing, and air to air combat. With the exception of torpedo bombing, all again use the superiority game mechanism with either the BOMB COMBAT TABLE for level and dive bombing or the GUNFIRE COMBAT TABLE for air to air combat.

Interlude – Two Tables or Four?

[In another bit of some design genius, Newberg presents two tables in the charts section that are actually used in multiple ways. The BOMB COMBAT TABLE and the GUNFIRE COMBAT TABLE are the same table with the Bomb Attack Superiority columns across the top and the Gunfire Attack Superiority columns across the bottom. A similar arrangement is used for the TORPEDO COMBAT TABLE and the COLLISION TABLE. The fact that Newberg can make the results of two tables work across multiple types of combat (yes, collisions can be viewed as a type of combat) should be inspiring for other designers who often, in these days of grander production values, all too often just go with another, and another, and yet another table.]

The primary difference in the aerial combat game mechanisms are not which combat table is used but in how the different aircraft must maneuver in an attack. Level bombers must enter from the bow/stern hex of the target. Dive bombers must end their movement in the target hex. Torpedo bombers must strike from the port/starboard hexes. Simple rules that are very playable yet add just a dash of thematic flavor to a battle.

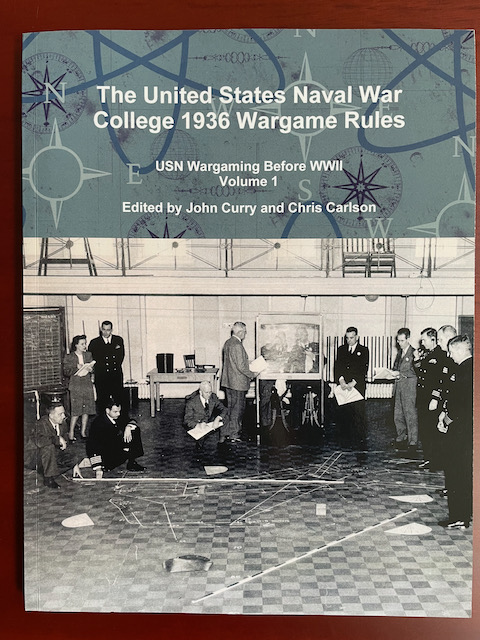

If there is one aerial combat rule that will almost certainly irk the simulationist wargamers who grew up on flight deck handling games like Flat Top (S.Craig Taylor originally for Battleline in 1977) it has to be IJN / Kriegsmarine 8.6.1, Torpedo! 9.6.1 which specifies, “AC [carrier-based] type aircraft may make any number of bomb attacks but must land on their home vessel and remain there for 5 turns to rearm after each attack before they may make another” (Kriegsmarine 8.6.1). Recall that each turn is only 90 seconds making 5 turns a mere 7 minutes 30 seconds. This is an extremely optimistic (unrealistic?) timeline; in the midst of the Battle of Midway the Kido Butai averaged 20 minutes—roughly 13 turns—between recovery and launch of a Combat Air Patrol (CAP) fighters (Parshall, J., & Tully, A. (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Potomac Books. p. 230). In the U.S. Naval War College rules of 1936, the assumed refuel/rearm time for a fighter squadron landing on a carrier was also 20 minutes but 30 minutes (20 turns) for a dive or torpedo bomber squadron (Curry, J., & Carlson, C. (2019). The United States Naval War College 1936 Wargame Rules. The History of Wargaming Project. p. 114). While the shorter refuel/rearm time in Newberg’s games is patently unrealistic, it was likely again a nod to playtesters who wanted to rapidly recycle aircraft back into battle if for no other reason than for F-U-N.

Short rules for the longest lance

The game mechanisms Newberg uses for torpedo combat in IJN / Torpedo! / Kriegsmarine / Schnellboote are a gross simplification of reality, showing that once again playability over strict simulation was almost certainly a driving design factor.

In Newberg’s quartet of games, launching a torpedo is simply a matter of the player indicating an edge hex that torpedo salvo is aimed at. The torpedo marker will move a certain number of hexes (torpedo movement factor) for a certain number of turns (torpedo duration factor) until it either passes within one hex of a ship or exits/expires. If the torpedo was sighted there is a chance for the target ship to evade using the TORPEDO EVASION TABLE. If not, the TORPEDO COMBAT TABLE is consulted to determine damage. Damage is expressed in terms of flooding points which sink a ship once a given amount (dependent on target type) are accumulated.

In the various Designer’s Notes, Newberg explains some of the design decisions made with regards to torpedoes:

IJN: All torpedoes are treated as if launched form centerline tubes. The artist couldn’t find room on the counters for the extra numbers to keep track of where the tubes might be and the players found it to be a good deal of extra paperwork, especially when dealing with reloads. We compensated for this a bit with the torpedo stacking limit [four torpedo markers in a single hex]. The Limit itself was based on normal firing angles for torpedo spreads and the effect on vessels movement from a torpedo hit, in addition to the size of the hex compared to that of the vessels.

IJN, 16.0 Designer’s Notes

One problem facing the user of a conventional torpedo is that the target might not get to a location at the same time a torpedo does. This problem has two solutions: Either fire from such close range that the target has very little time to change course, or fire from long range carefully computoing the locus at which the target will most likely be. By making torpedos distinct units, this situation can accurately be simulated. Players must either risk detection at short range to get a “sure” shot, or fire from afar with greater safety but less chance of success.

Torpedo!, 18.0 Designer’s Notes

And as a final addition for the effects of this scale torpedoes were handled in a somewhat different manner. They are the ultimate ship killers no matter what the delivery platform but the player always finds himself in the position of wanting to get just a few hundred yards closer so he can be sure they hit. Just the kind os comment one constantly reads in actual action accounts by participants.

Kriegsmarine, 16.0 Design Notes

In effect, unless you are close enough to get the torpedo there in the turn of launch, you have to fire towards where you think the target will be when the torpedo gets there.

Schnellboote, 15.0 Design Notes

Perhaps the most famous torpedo of World War II is the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 61 cm (24″) Type 93 (1933) more commonly known as the Long Lance. Again, we go to Parshall in Fighting in the Dark for a description:

Commonly known after the war as the “Long Lance,” the Type 93 was hands down the finest torpedo of World War II. It was huge—9 meters long (25.5 feet), weighing 2,700 kg (5,952 pounds), and carrying a whopping 490 kg (1,080 pound) warhead. Powered by kerosene and 300 kg of pure oxygen compressed to 3,200 psi, the new version effectively had eliminated more than a ton of nitrogen from the torpedo’s weight profile. It engine was extremely powerful—520 brake horsepower—capable of hurling the torpedo through the water at up to 50 knots. It left practically no wake; only the slightest sheen of lubricating oil was visible at short range in daylight under the right conditions. At night it was utterly invisible. What made the Type 93 such a game-changer, however, was its extreme range—up to 40,000 meters, at a time when contemporary 53-cm torpedoes had a maximum range of perhaps eight thousand meters. This exceeded the range of the very largest battleship guns, and gave the Japanese navy a long-range underwater strike capability that no other navy possessed.

O’Hara, p. 151

The torpedo factors used in the series are very accurate. With a speed of 25 hexes per turn (50 knots) and duration of nine turns the Mk 93 in the series has a maximum range of 22,500 yards [225 hexes]. Compare that performance to the U.S. Navy 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 15 with game factors of speed 13 and a duration of 11 that converts quite accurately to 26 knots for 14,300 yards [143 hexes]. Those ranges seem extreme until one recalls that at the Battle of Savo Island (8-9 Aug 1942) the Japanese sighted the Americans at a range of 12,500 yards (125 hexes) which was about the range the first salvo of Mk 93 torpedoes were launched from.

While Newberg called torpedoes “ship killers” in Kriegsmarine a look at the damage results in the TORPEDO DAMAGE TABLE seemingly show that it takes more torpedo hits to sink a warship than may have been the historical condition. Take for example the Second Battle of Guadalcanal (14-15 Nov 1942) where a single Mk 93 hit—and sunk—USS Walke. In the game series that attack would see the Mk 93 torpedo attack factor of 11 matched against the destroyers torpedo defense factor of 1 for an attack superiority of +10. Consulting the TORPEDO COMBAT TABLE the die roll would use the +12 column where the damage ranges from 2 to 7 Flooding Points of damage scored. A destroyer (DD) class ship requires 12 or more flooding points of damage to sink making a single-shot Mk 93 kill unachievable.

As naval historian Trent Hone points out in his chapter “Mastering the Masters: The U.S. Navy, 1942-1944” in Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night: 1904-1944, by late 1942 new instructions for Night Search and Attack were promulgated which emphasized that, “An ‘ideal’ squadron attack would involve three destroyer divisions approaching ‘from widely separated sectors’ and hitting the enemy ‘with torpedoes before being detected” (O’Hara, V. P., & Hone, T. (2023). Fighting in the Dark: Naval Combat at Night: 1904-1944. Naval Institute Press. p. 190). Though Newberg’s design seemingly over emphasizes short-range gunnery battles at night, it actually comes fairly close to showing the doctrinal emphasis on night-fighting with torpedoes at longer ranges. Taken as a whole, the torpedo rules are again a good example of playability balanced against realism, with some obvious favoritism towards playability.

Ten-second wargaming

In late 1943, then-Capt. Arleigh burke was mentoring a young ensign in tactical decisionmaking. Burke, a seasoned veteran of Cape St. George and Empress Augusta Bay, asked the young ensign to tell him “the difference between a good officer and a poor one.” The ensign hesitated, and then described the importance of “aggressiveness, technical proficiency, command presence, knowledge of human nature” and other leadership qualities that had been emphasized in his education. Burke listened patiently and then said, “The difference between a good officer and a poor one is about 10 seconds.”

O’Hara, p. 251

Whether Newberg knew it or not, the quartet of tactical naval wargames IJN, Torpedo!, Kriegsmarine, and Schellboote channels Admiral Arleigh Burke. These four naval wargames, focusing on night naval actions by smaller units, present themselves though a game design that focuses on quick, decisive, if not a bit elusive, combat actions. The design even purposefully(?) distorts ranges and time in the name of playability. While simulationist wargamers may be offended, players who are looking to play a wargame and accept a design that is evocative of a condition will very likely find these games enjoyable gems. Instead of complaining about production quality, I hope that modern gamers can properly acknowledge the design decisions made that build into a very playable wargame.

For myself, this deeper look at Stephen Newberg’s quartet of naval tactical warfare games published through Simulations Canada in the late 1970s and early 1980s led to my reevaluation of my BGG ratings. Whereas I previously rated these games a 6 (“OK – Will play if in the mood”) I have upped my ratings to 7 (“Good – Usually willing to play”) which is a hair above my BGG average of 6.61 for boardgames and almost a whole point above the BGG average rating of 6.1. I can see glimpses of excellence in the game design…and I like them.

Feature image courtesy RMN

The opinions and views expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and are presented in a personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Navy or any other U.S. government Department, Agency, Office, or employer.

RockyMountainNavy.com © 2007-2024 by Ian B is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ![]()